August 3, 2017

The man-made problem is an environmental disaster and an economic threat.

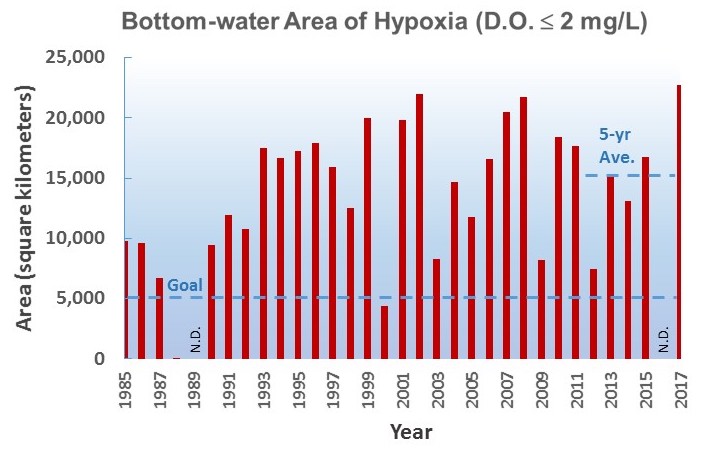

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced Wednesdaythat this year’s “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico is the largest ever measured.

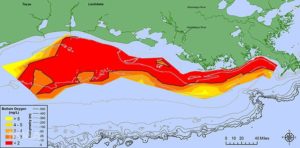

Stretching from the coast of Louisiana at the Mississippi River Delta westward to the shores of Texas, the area of severe hypoxia — when the water is so depleted of oxygen that it can’t sustain fish and marine life — encompasses 8,776 square miles. That’s roughly the size of New Jersey (or more than 4 million football fields, if that’s any easier to grasp).

Previously, the record for largest dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico was measured in 2002 at 8,497 square miles. The average size of the dead zones in the past five years is 5,806 square miles, according to NOAA.

The dead zone in the Gulf has become a worrisome annual phenomenon mainly due to excess nitrogen and other nutrients that run off from rivers like the Mississippi into the Gulf and feed the growth of algae. When the massive blooms of algae and phytoplankton die, their decomposition consumes all the oxygen in the ocean, creating a hypoxic area, or dead zone. Fish that can swim away do, but the organisms that can’t, including the plants that fish feed on, die.

These “biological deserts” are bad for fish and fish eaters alike. Hypoxia hurts the Gulf of Mexico’s commercial and recreational fishing industries, which are still recovering from recent hurricanes and oil spills. The Gulf produces more than 40 percent of the nation’s domestic seafood supply and, according to the EDF, generates billions of dollars a year in wages for the fishing and tourism industries across five states. An NOAA-funded study by Duke University found that hypoxia in the Gulf in particular drives up the prices of large shrimp, creating an economic ripple effect on seafood markets and consumers.

Almost every summer since 1985, NOAA has sponsored research and monitoring of hypoxia off the coast of Louisiana. It says the record-breaker this year is a result of higher rainfall in the Midwest and heavier river flows than usual.

The most problematic nutrients that end up in the Gulf and feed the algae are nitrogen and phosphorous, which run off from myriad big and small farms across the country. Farmers use the nutrients as fertilizers on their fields, but rain can then wash that fertilizer into nearby streams and rivers. The Nature Conservancy estimates that the Mississippi River and its tributaries drain from 41 percent of the United States, delivering quite a lot of nutrient pollution to the Gulf.

A recent report by the environmental group Mighty Earth blames much of the nutrient pollution in the Gulf on the meat industry. The report implicates the entire meat supply chain, but it identifies the fertilizer runoff in livestock feed production as well as the dumping of cattle manure as the biggest sources of pollution. The report calls on companies like Tyson Foods to reform unsustainable practices.

There have been organized efforts to minimize the ecological disaster caused by nutrient pollution, but they have not been very successful.

Don Scavia, a professor at the University of Michigan and former top scientist at NOAA, wrote in a blog post: “In spite of more than 30 years of research and monitoring, over 15 years of assessments and goal-setting, and over US$30 billion in federal conservation funding since 1995, average nitrogen levels in the Mississippi have not declined since the 1980s.”

The Nature Conservancy has seen some positive results through partnerships with big players in the agriculture industry (which the organization advises and advocates for more environmentally friendly land use and crop management practices). But Scavia suggests that a purely voluntary approach to curbing nutrient runoff is inadequate. A broader national approach that includes more enforced regulations and a modification of the American diet to consume less meat is necessary.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration is unlikely to be of much help. The Environmental Protection Agency’s website describes nutrient pollution as “one of America’s most widespread, costly and challenging environmental problems,” but Trump’s fiscal year 2018 budget request would cut a $165 million grant program specifically meant to deal with the problem of non-point source nutrient pollution.

Source: https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/8/3/16089296/gulf-of-mexico-dead-zone