August 6, 2017

Sixteen years after voluntary limits on fertilizer went into effect, the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico this year is the largest since scientists began measuring it in the mid-1980s.

The low-oxygen zone this year covers at least 8,776 square miles, which is as large as the state of New Jersey. The dead zone is likely even larger than that, but the research ship had limited time to monitor it.

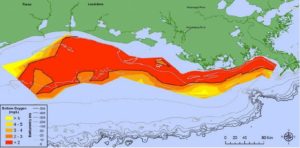

Researchers measured the largest dead zone since 1985 during their 2017 cruise, with this year’s low-oxygen area totaling 8,776 square miles, larger than the state of New Jersey. Red on the map indicates hypoxia, where the oxygen level is less than 2 parts per million.

It has been clear for some time that the voluntary reductions of fertilizer use along the upper Mississippi River weren’t sufficient to reduce the dead zone. But that is reinforced by these measurements showing it has grown dramatically.

When the fertilizer limits were put in place in 2001, the goal was to reduce the size of the dead zone to no more than about 1,900 square miles by 2015.

That didn’t happen. And this year’s dead zone is more than four times larger than the goal.

Between 2010 and 2015, the dead zone averaged about 5,500 square miles. The annual area of low oxygen in the Gulf shrank to 2,889 square miles in 2012 — one of the smallest dead zones in almost three decades. But that was due to a drought up river, not to the fertilizer measures.

The voluntary limits in the Mississippi River basin have failed, Donald Scavia, University of Michigan environmental engineering professor, wrote in a recent opinion essay for The Conversation. “In spite of more than 30 years of research and monitoring, over 15 years of assessments and goal-setting, and over $30 billion in federal conservation funding since 1995, average nitrogen levels in the Mississippi have not declined since the 1980s.”

The task force leading the effort to reduce nitrogen recently extended the goal for shrinking the dead zone by 20 years, to 2035, he said.

New modeling “shows that it would take a 59 percent reduction in the amount of nitrogen entering the Gulf of Mexico to reach the task force’s goal,” Mr. Scavia said. He argues that government needs to make the reductions legally binding instead of voluntary.

A 2015 study in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association laid out other strategies that, combined with limits on fertilizer use, might have a significant impact on the dead zone.

The scientists recommend enhancing drainage ditches, restoring wetlands on some marginal cropland and reconnecting rivers to their flood plains.

That basically would create wetland filters to remove nitrogen and other nutrients before water drains off of fields and into waterways, the study said. The land in question isn’t very productive now, so there would be minimal effects on farm production, it said.

The main causes of the dead zone, which was discovered in the 1970s, are well defined. Nitrogen and phosphorus from farmland flow into the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers and eventually the Gulf of Mexico, where the nutrients cause massive algae blooms. When the algae die and decay, oxygen is sucked out of the water. The resulting hypoxia kills bottom-dwelling marine life and forces fish and shrimp to move to areas where there is more oxygen — which means fishers have to go farther to harvest them.

The push to reduce nitrogen and phosphorous runoff was complicated by the increase in corn production for ethanol, which the federal government encouraged. The growth in ethanol resulted in 15 million new acres of farmland being planted with corn in 2007 alone.

The Environmental Protection Agency needs to take another look at this issue. Reducing the dead zone is essential to the health of the Gulf, but it’s headed in the opposite direction.

There is 16 years of evidence that the current strategy isn’t working. It’s time for a different approach.

Source: http://www.nola.com/opinions/index.ssf/2017/08/gulf_of_mexico_dead_zone.html