By Todd C. Frankel / The Washington Post

March 14, 2018

By Todd C. Frankel / The Washington Post

March 14, 2018

A picaresque tour of infrastructure reveals a struggle for control all along America’s great river, full of questions about what it once was, doubts about what it will become and who will pay for any of it.

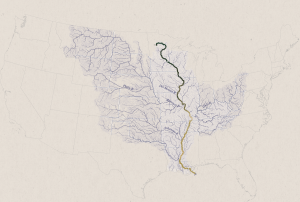

ALONG THE RIVER — The Mississippi runs the spine of America, touching 10 states and draining waters from 21 more, a vast waterway with a rich mythology, a sometimes powerful beauty and an always alarming propensity to flood.

Nearly 30 locks and dams hold back water in the river’s upper reaches. Every river bend to the south is lined by concrete to slow the water’s corrosive force. Levees corset thousands of miles of riverbanks and 170 bridges run above. All of this infrastructure is aimed at permitting barge traffic and protecting farms and cities. Most of it is decrepit.

Now, with President Trump’s push for a $1.5 trillion infrastructure plan, there are hopes of billions to fix up the Mississippi. But there are clashes over which projects to pursue, and no agreement on how to pay for any of it.

A move to tame one portion of the river can create chaos for people somewhere else along its 2,350-mile path, and in that precarious balance is the key to understanding the competing interests and enduring problems that vex the entire country.

“To understand America at this time,” says R.D. James, a Missouri farmer and new Army assistant secretary overseeing its Corps of Engineers, “you have to understand the river.”

At the same time, it’s clear that the river itself has changed.

“It doesn’t behave like it used to,” said John Carlin, a towboat pilot who has worked the Hannibal, Mo., riverfront for more than 40 years. “Seems like it doesn’t take much to get out of control.”

Now, the Mississippi is flooding again. Last week, after a deluge of late-winter rain, the Corps opened a massive floodway just above New Orleans, an emergency relief valve that it has been forced to use with increasingly regularity — three times in just the last seven years.

Infrastructure is a bureaucratic word, a way of describing human efforts to impose order on nature. More than almost anything government does, the effects of the infrastructure it builds can be felt for generations. Earth is moved. Water redirected. Tunnels dug. Roads paved. It is man’s hubris on naked display. Sometimes, the infrastructure turns out to be the enemy, and that fact makes the people working and living along the Mississippi wary of the promises coming from Washington.

Some river watchers perked up when Trump mentioned “waterways across our land” as part of his infrastructure target list during his recent State of the Union speech. That sounded like good news. But Trump’s plan mostly scales back the government’s long-running role in charting the Mississippi’s course, calling for more private investment and less federal oversight along the river.

That, many here say, will create a host of new problems.

“It’s disappointing,” said Mike Toohey, president of the Waterways Council, a barge industry group, echoing the reaction of many people who use the river. “We’re running on an interstate of water. And we’re always being overlooked.”

The trouble with controlling the Mississippi today is that it has evolved into three different river systems.

The Mississippi River Watershed

The Upper Mississippi is a string of slack-water pools held behind dams, with water so placid that water skiing was invented there in 1922.

The middle portion is a mishmash of wing dikes and arched chevrons — man-made structures to “train” the river. Here, it is artificially narrowed, only half as wide in St. Louis as it was in the early 1800s.

The truly fearsome Mississippi doesn’t start until the confluence with the Ohio River at Cairo, Ill., where the water emerges like a monster on par with the Amazon or Congo rivers. The Mississippi then runs to the Gulf of Mexico, hidden behind an extensive levee system built after the Great Flood of 1927, a disaster that displaced 1 percent of the country’s population as levees fell like toppled dominoes.

That flood’s legacy still guides how the river is controlled today.

The Army Corps of Engineers oversees most of the river’s infrastructure and runs it with a battle general’s intent. It’s the Corps that operates the locks and dams, that built the levee system in the Lower Mississippi; it maintains the tools used to control the water levels throughout and regulates levees farther north.

But a growing number of critics say the Corps’ flood-fighting efforts make flooding worse.

“It’s like fighting the moon,” said Robert Criss, a hydrogeologist at Washington University in St. Louis, who studies the river running just a few miles from his office door. “It’s stupid to fight.”

And it can look like a losing battle.

…

—-Click the link below to read the full article—-