July 16, 2017

Four generations of the Olander family have shrimped the coast of Louisiana, but now Thomas Olander, chairman of the Louisiana Shrimp Association, is trying to convince his own son to get out of the family business while he’s still young as the Mississippi River spews poison into the Gulf of Mexico.

The shrimp are smaller, the young fish are dying off and the oysters have been beaten back. Crabbers say they’re pulling up traps filled with dead crustaceans.

The technical, scientific phrase for what’s going on is hypoxia: oxygen levels in the water unsupportive of most life. But everyone calls the hypoxic areas by a more grim name.

This summer’s Gulf dead zone is projected to be the worst ever, and fishermen, shrimpers, crabbers, oystermen and others who rely on the seafood industry are feeling the hurt.

“It’s a ripple effect. From the hardware stores to the restaurants … everybody in the community (is affected,)” said Louisiana Shrimp Association president Acy Cooper.

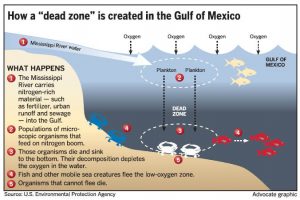

Each spring, rains wash fertilizer as well as human and animal waste into the Mississippi River and its tributaries from 31 states. The U.S. Geological Survey has estimated the amount of fertilizer washing from the Mississippi and Atchafalaya into the Gulf this year would fill 2,800 train cars.

When the river empties into the Gulf of Mexico, algae feed on the nutrient-rich material but die when it is all consumed. As they decompose, the algae simultaneously make the water more acidic and deplete the oxygen levels, leading to hypoxia.

Most organisms can’t survive in these dead zones. Some animals like fish and shrimp can escape — though the hypoxia may retard their growth — but stationary species like clams and oysters just die.

LSU professor Nancy Rabalais has been studying the dead zone for decades, and other scientists rely on her annual forecast to predict the extent of the hypoxia. The dead zone will peak in late July and early August, and Rabalais expects it to become approximately the size of the state of Vermont, based on the amount of chemicals flowing down the Mississippi, most of which can be traced to fertilizer for corn and soybean farming.

There was some question as to whether tropical storm Cindy may have stirred up the water and caused the dead zone to dissipate, but it appears to have reformed, Rabalais said. If her projection holds, the 2017 dead zone will be the largest on record.

While Louisiana faces the cost of hypoxia, few of the nutrients originate here. Blame the midwestern “I” states — Indiana, Illinois and Iowa — says chemist Wilma Subra of the Louisiana Environmental Action Network.

“Louisiana’s not contributing that much to the dead zone but we are the recipients, so we have to bear the burden,” she said.

Even though the dead zones represent a massive problem, many officials said possible solutions are not getting the financial support they need.

“This was poorly understood, say, 15 to 20 years ago,” said Louisiana Sea Grant fisheries agent Rusty Gaudé.

In 1997, a National Hypoxia Task Force was established to reduce the Gulf dead zone through steps like restoring wetlands and improving agricultural irrigation, said Doug Daigle, founder of the Louisiana Hypoxia Working Group.

However, the national group hasn’t pursued all its options and so far has missed its own benchmarks, he said.

Smart people have come up with good ideas like limiting fertilizer use and creating more buffer zones to trap agricultural run-off, said Subra, the chemist. However, they haven’t been getting the money needed to take meaningful action, she said.

The mid-Atlantic has been much more aggressive in policing its waters. Between the states of New York and Virginia, everything eventually drains into the Chesapeake Bay, which has historically had its own problems with hypoxia. It’s a smaller and less complex watershed, but leaders have successfully cleaned it up, and now nitrates and phosphates are down and oyster and crab populations are up. The local striped bass was even brought back from the edge of extinction, Chesapeake Bay Foundation Director Will Baker and senior scientist Beth McGee told a group of environmental reporters last month.

It’s taken concerted action. Wastewater treatment plants have been upgraded; facilities like Washington DC’s are state of the art, McGee said. In Virginia, the government pays ranchers who put fencing along streams to keep livestock out of waterways and keep them clean. The federal Environmental Protection Agency withheld millions of dollars in funding to Pennsylvania one year when it missed a pollution benchmark.

And while the Chesapeake Foundation leaders are pleased with the progress, they’re also keeping a watchful eye on the Donald Trump administration, which has signaled its desire to cut funding from programs like theirs and ones aimed at keeping the Great Lakes clean.

The Trump administration is causing “a lot of uncertainty about what’s going to happen” to address hypoxia, said Daigle of the Louisiana working group.

A few people interviewed for this story — including state Wildlife and Fisheries biologist Jeff Marx — wondered aloud if there might be an upside to the dead zone. If shrimp have to escape low-oxygen waters, they may be herded into concentrated areas where an industrious shrimper could catch a massive haul.

Rabalais, the LSU scientist, disagreed.

“Shrimp production is hampered (by hypoxia) …. We know that,” she said. “It’s not going to improve until there’s a good effort to reduce the nutrients.”

The men out in the boats didn’t buy the argument either.

Delacroix-based shrimper Vernon Alfonso said members of his family have been pulling up traps filled with dead crabs. Even the shrimp he does catch are smaller.

Duke University researchers found that “low oxygen conditions slow shrimp growth, leading to fewer and more expensive large shrimp,” the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration wrote in a January report.

“The consumers are gonna pay for it. To what extent, I don’t know,” warned Cooper, the Shrimp Association president.

Gaudé, the Sea Grant agent, said the dead zone also affects the ability of fish to reach their spawning grounds and for juveniles to survive and mature. Larger fish can swim out of a hypoxic area, but younger, smaller individuals “are at the mercy of the currents,” he said.

The dead zones are probably limiting the range of oysters, as well, said John Lopez, program manager at the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation. The animals can already be found around the Biloxi Marsh, but they should appear farther out into the Chandeleur Sound, he said. Hypoxia seems to be limiting their range, suppressing their population and killing off young oysters.

And that causes a ripple effect. For fishermen, it’s economic, and their trouble affects the people they pay to fuel their boats and the grocers who buy their catch. For scientists, its an ecological effect as hypoxia throws the food chain off kilter.

People who study the dead zones and care about reducing hypoxia need to do a better job getting their message out to the public, Lopez concluded.

“Frankly, I’m a little taken aback,” he said. “I don’t think we fully appreciate it.”

Source: http://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/article_1071281e-6661-11e7-ae09-ffd0743dee34.html