Mark Schleifstein | NOLA.com 1 August 2024

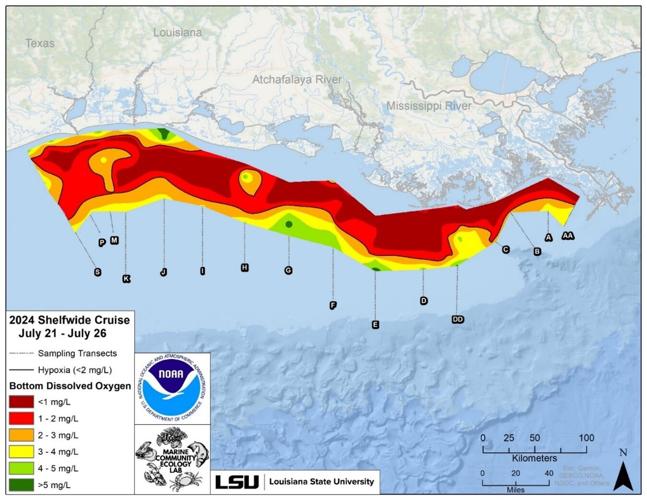

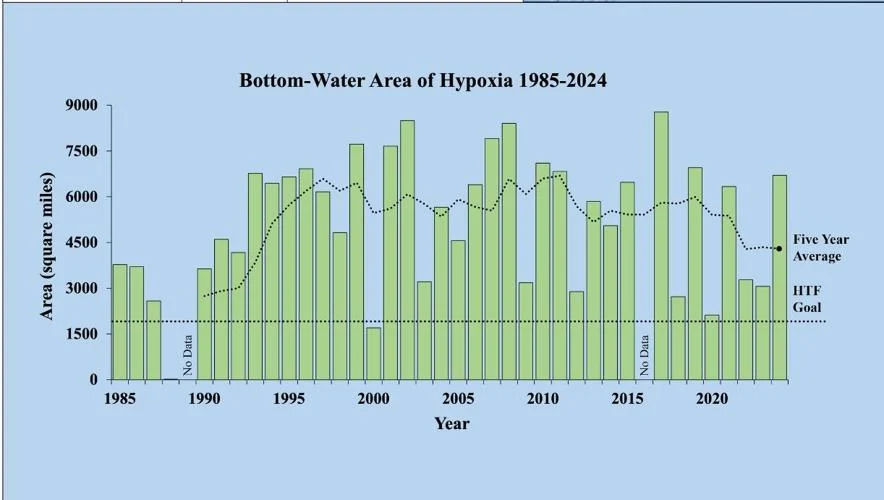

The annual “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico along Louisiana’s coast – an area where low to no oxygen in the deepest water can kill fish and other marine life – covered 6,705 square miles this summer, the 12th largest measured during 38 years of annual cruises, federal officials announced Wednesday.

That’s nearly 40 times the size of the city of New Orleans, nearly as big as the state of New Jersey, and more than twice the size of the low-oxygen area last year.

And when combined with previous years’ measurements, the five-year average for the low-oxygen zone is now 4,298 square miles, more than twice the size of a goal to reduce it to less than 1,900 square miles by 2035, set by a federal-state nutrient reduction task force.

It also was nearly 1,000 square miles larger than NOAA’s pre-measurement forecast, and nearly 4,700 square miles larger than a new pre-measurement forecast method created by LSU scientists that predicted warmer water temperatures caused by global warming would result in less algae being formed this spring and summer.

“It’s a symptom of an ecosystem that is not functioning well, which is not good for living resources,” said Nancy Rabalais, a Louisiana State University biologist who started the annual hypoxia mapping cruises in 1985, during a Wednesday online news conference with officials from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Environmental Protection Agency and other researchers. “In fact, any fish that can swim out of the area does swim out, and that includes blue crabs and shrimp, as well.”

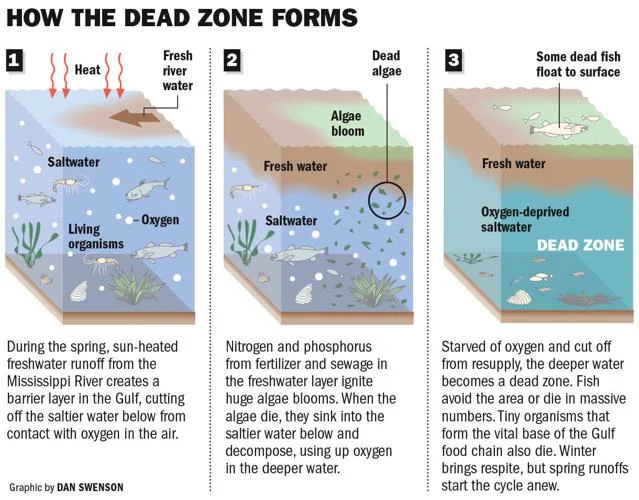

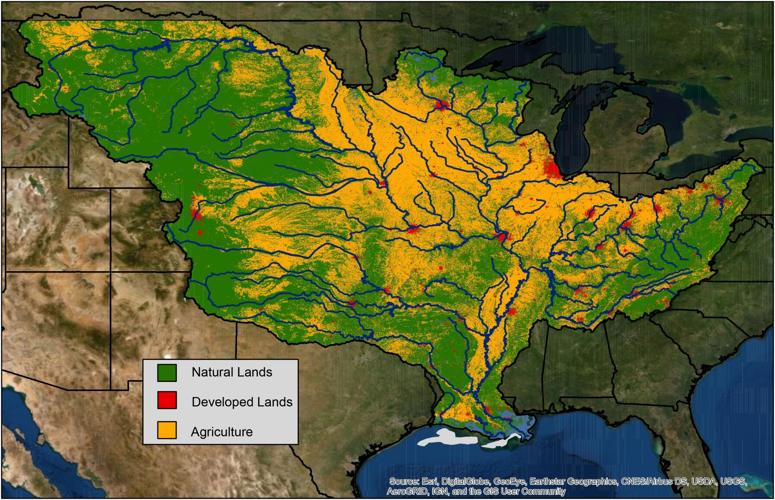

The low- to no-oxygen levels in bottom waters is a condition called hypoxia. It’s directly linked to nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients contained in fertilizers applied to farmland in the Midwest, with a lesser contribution of nutrients in sewage released from public treatment plants and in runoff from home treatment systems throughout the Mississippi River basin.

The basin includes all or parts of 31 states, an area spanning 1.2 million square miles. The river’s freshwater and nutrients enter the Gulf of Mexico at both the river’s mouth south of New Orleans and through the Atchafalaya River basin to the west.

That freshwater creates a layer atop heavier, more dense salt water along the Gulf coastline, and the nutrients feed large blooms of algae that then die and sink to the bottom, where they decompose, using up oxygen.

The low-oxygen conditions continue until storms or hurricanes mix freshwater at the surface containing oxygen with the deeper water.

The Mississippi River watershed, which encompasses over 40% of the continental U.S and crosses 22 state boundaries, is made up of farms (yellow), cities (red), and natural lands (green). Nitrogen and phosphorus pollution in runoff and discharges from agricultural and urban areas are the major contributors to the annual summer hypoxic dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico (gray). (USGS)

“The area of bottom-water hypoxia was larger than predicted by the Mississippi River discharge and nitrogen load for 2024, but within the range experienced over the nearly four decades that this research cruise has been conducted,” Rabalais said.

In a separate news release from LSU and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, which operates the Pelican research ship that conducted the survey along the Louisiana and eastern Texas coasts between July 21 and 26, researchers said the nutrients in the river water were primarily nitrogen compounds.

The river’s discharge rate was lower than average for May of this year, usually a good predicter of the low-oxygen zone, but was higher than average for July. And monitoring during the cruise indicated that the warmer freshwater at the surface, rich in oxygen, was not mixing with the bottom, saltier water that contained low oxygen levels.

And while U.S. Geological Survey officials contend that the amount of nutrients in the Mississippi have dropped by 20%, compared to historic levels, the LSU researchers point out that the USGS comparison is based on levels in the late 1970s.

“The long-term nitrogen loading from the Mississippi River to the northern Gulf of Mexico has not decreased since the adoption of the Hypoxia Action Plan in 2001,” the LSU report said. “There remains a need for nutrient reduction mitigation within the Mississippi River watershed for the environmental and human health within the watershed and for the reduction of low dissolved oxygen in the northern Gulf of Mexico.”

Iowa Agriculture Secretary Mike Naig, and Environmental Protection Agency Acting Assistant Administrator Bruno Pigott, co-chaire of the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force, pointed to $60 million in federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding for conservation efforts within the basin aimed at reducing nutrients as a key strategy in meeting the 2035 goal.

Naig also emphasized the need to develop reduction strategies while recognizing the river’s importance as a shipping channel to the world, including the movement of 92% of the nation’s agricultural exports and 89 million tons of freight, representing $405 billion a year.

But Midwest states also have seen nutrient improvements, he said, including the removal of 15 Minnesota lakes from a list of those impaired by nutrient pollution, and similar successful reduction efforts in Indiana, Illinois, Tennessee, Ohio, Missouri and Kentucky.

Still, USGS program manager Lori Sprague pointed out that both nitrogen and phosphorus levels will need to be reduced by another 48% to reach the 2035 goal. And federal, state and research participants agreed that more successes are needed in obtaining funds to pay for reduction projects.

Naig provided a list of state efforts aimed at reducing nutrient pollution:

- Iowa — has broken records for conservation measure adoption during the past two years, and expects a third record this year. The state is also moving closer to a goal of constructing 30 wetland projects aimed at capturing nutrients a year.

- Minnesota – in addition to the lake measures, the state has spent over $300 million since 2018 on watershed improvements that have reduced river nitrogen loads by nearly 80,000 lbs/year and phosphorus by about 40,000 lbs/year.

- Illinois – through the state’s pollution discharge program, industries have achieved a 37% reduction in total phosphorus discharges since 2011, exceeding a 25% goal by 2025. The state also has hired 40 conservation planners.

- Tennessee – the state’s Department of Agriculture spent nearly $600,000 in the past year on cover crops in watersheds known to have high soil erosion rates. Cover crops help prevent nutrient runoff.

- Ohio — 535 producers in 64 Ohio counties enrolled 503,000 acres this spring in a voluntary nutrient management planning and implementation program.

- Missouri – In fiscal year 2024, the state is spending $49.5 million on soil and water conservation and nutrient loss reduction practices, an increase of $9.5 million from fiscal year 2023.

- Louisiana — Two projects targeting nutrient reduction have been funded in northeast Louisiana..

- Kentucky – the state paired over $1.6 million in agriculture and infrastructure funding to improve wastewater treatment and reduce soil erosion in Boyle County.

- Indiana — A recent survey found that 1.7 million acres of farmland are now cover cropped. In 2023, landowners installed more than 50,000 conservation practices.

- Arkansas – The state saw about 800 attendees at 30 Arkansas Nutrient Reduction Strategy events, part of the state’s education and outreach program.